As a part of the Permanent Residency (PR) application, an Immigration Medical Exam (IME), is must for the primary applicant and all family members (spouse or common-law partner, dependent children, and their dependent children.) listed in the application, even if they are not accompanying. For express entry applicants an upfront medical examination confirmation is mandatory for the application to be complete for the completeness check. If either the primary applicant or any of the family members, whether accompanying or not, is medically inadmissible into Canada, all members, including the primary applicant will be inadmissible. Therefore, after age, medicals are the most important aspect on which an applicant has virtually no control.

As a part of the Permanent Residency (PR) application, an Immigration Medical Exam (IME), is must for the primary applicant and all family members (spouse or common-law partner, dependent children, and their dependent children.) listed in the application, even if they are not accompanying. For express entry applicants an upfront medical examination confirmation is mandatory for the application to be complete for the completeness check. If either the primary applicant or any of the family members, whether accompanying or not, is medically inadmissible into Canada, all members, including the primary applicant will be inadmissible. Therefore, after age, medicals are the most important aspect on which an applicant has virtually no control.

If you are are concerned with your medicals, or have received a fairness letter, and want to obtain a copy of your medical assessment, or a copy of the medical examination submitted to IRCC, GET GCMS will be happy to procure it for you. Send a message to GET GCMS through our Contact US page to know how to go about obtaining medical documents from IRCC

This post covers the following:

1. Who can do your medical exam?

2. What is the Validity of a Medical Examination?

3. Can a previous medical examination be used?

4. How to get your medical exam

4.1 Upfront Medical Exam

5. What to carry with you for the Medical Examination

6. Medical inadmissibility

6.1 Danger to public health

6.2 Public Safety

6.3 Excessive demand on health and social services

6.4 Cost threshold

7. Procedural Fairness Protocol

8. Forms, documents and templates

8.1 Immigration Medical Examination

8.2 Medical surveillance (forms and documents)

8.3 HIV: Automatic partner notifications (documents and template letters)

8.4 Medical refusals and procedural fairness (forms, documents and template letters)

8.4.1 Procedural fairness regarding a danger to public health and public safety

8.4.2 Procedural fairness regarding excessive demand on health (i.e., out-patient medication) and/or social services

1. Who can do your medical exam?

Medical examination for PR application can only be conducted by a physician who is on the list of panel physicians with IRCC. The panel physician only conducts the medical examination and send the report to IRCC. The panel physician does not make a determination about the admissibility. In case of any concerns or issues, IRCC will send a written communication to the applicant. The medical exam can be done by any panel physician anywhere in the globe. There is no requirement of having it done in the country of residence or citizenship. Further, if the application also has spouse and dependent children, they can get the medical examination done at different panel physicians.

2. What is the Validity of a Medical Examination?

The validity of the Medical Examination is 12 months. The applicant and his accompanying dependents have to land in Canada before the medicals expire. Therefore it is advisable to get the medical examination done right before submitting the eAPR for the express entry applicants. For non-express entry applicants, the medicals will be scheduled when requested by IRCC.

3. Can a previous medical examination be used?

Yes, if an applicant has submitted a medical examination certificate for some another program, such as student visa, previous PR application which was rejected etc. the same medical examination can be used for the current PR application. When submitting the application the applicant should upload the upfront medical confirmation certificate which was issued when the medical examination was done.

4. How to get your medical exam

There are two ways for getting the medical examination done.

- Wait for the instructions – This is applicable for Refugee asylum, spouse sponsorship and other categories. Here, the applicant will have to wait until IRCC sends in a document to get the medical examination.

- Upfront – Upfront Medical Examination (UME) is MANDATORY FOR Express Entry Applications.

4.1 Upfront Medical Exam

To get an upfront medical exam, contact a panel physician directly to schedule an appointment. After the medical examination is done the applicant is given a document confirming the medical exam. The applicant will have to upload the copy of the medical exam confirmation with the eAPR (electronic application). If the panel physician works with eMedical (An online tool that doctors approved by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) to do medical exams use to record and send Immigration Medical Exam (IME) results to CIC. It is mor

e accurate, convenient and faster than paper-based processing) a printout of the confirmation will be provided. This confirmation is also called the information sheet.

Once the applicant has the confirmation, the eAPR can be filed and the medical respite will be transmitted directly to IRCC.

5. What to carry with you for the Medical Examination

When an appointment is scheduled with a panel physician, the panel physician will provide the details of what all documents are required on the day of the medical examination. Usually the following are mandatory:

- Identification document – Passport;

- If an applicant wears an eye glass or contact lens, they should carry it along with them;

- Any medical reports or test results of an existing or cured medical conditions; and

- Fee.

- Four Passport photographs if the panel physician does not use eMedical. Most physicians using eMedical will take a digital picture on the day of the medical examination.

It is always better to schedule an appointment and ask for the required documents. Some panel physicians also ask for Invitation to Apply (ITA) Document.

6. Medical inadmissibility

Medical inadmissibility is one of the factors which is beyond the control of an applicant. It is therefore very important to understand what ailments can cause medical admissibility and what will not. Knowing this will also help applicants alleviate any confusion and address unrealistic expectations. The panel physician DOES NOT make any decisions on medical inadmissibility. The Panel Physician merely sends the completed immigration medical examination report to IRCC. The IRCC medical officer reviews the medical examination report. This process is referred to as an immigration medical assessment. Upon completion of this assessment, the assessment results are entered in GCMS, which are then finalized by the visa office where the application is being processed. An applicant may be inadmissible on health grounds under A38(1).

A38(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act states:

Health Grounds

• 38(1) A foreign national is inadmissible on health grounds if their health condition

(a) is likely to be a danger to public health;

(b) is likely to be a danger to public safety; or

(c) might reasonably be expected to cause excessive demand on health or social services.

It is important to understand what each of these factors listed in A38(1) pertain to.

6.1 Danger to public health

For inadmissibility under the ‘Public Health’ factor, it is evaluated whether the applicant is affected or carries any communicable disease; and the impact that the disease could have on other persons living in Canada. (R31(b-c)).

The conditions which are likely to be a danger to public health are, active Pulmonary Tuberculosis (TB) and untreated Syphilis. If the applicant has either or both of these conditions, they will likely be found inadmissible on the grounds of danger to public safety, unless the applicant is treated according to the standards laid down by Health Canada. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is not considered a danger to public health.

6.2 Public Safety

For inadmissibility under ‘Public Safety,’ the risk of a sudden incapacity or of unpredictable or violent behaviour of the applicant that would create a danger to the health or safety of persons living in Canada is considered. (R33(b))

Conditions that are likely to cause a danger to public safety include serious uncontrolled and/or uncontrollable mental health problems such as:

- certain impulsive sociopathic behaviour disorders;

- some aberrant sexual disorders such as pedophilia;

- certain paranoid states or some organic brain syndromes associated with violence or risk of harm to others;

- applicants with substance abuse leading to antisocial behaviours such as violence, and impaired driving; and

- other types of hostile, disruptive behaviour.

For both these factors listed above, ‘Public Health’ and ‘Public Safety’ the wealth of the applicants is irrelevant. The Supreme Court of Canada in Hilewitz v. Canada, 2005 SCC ¶ 88 held that, “[t]he chief responsibility of the medical officer in such cases is to assess the danger to public health or safety. Wealth, regardless of how rich the applicant is, is irrelevant to this assessment.”

6.3 Excessive demand on health and social services

Even in a scenario where the applicant may not have any communicable disease and may not be a threat to public safety, if the applicant suffers from any medical condition, which is likely to place excessive demand on health and social services, will render the applicant medically inadmissible. Section 1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPR) defines “excessive demand” as

-

a demand on health services or social services for which the anticipated costs would likely exceed average Canadian per capita health services and social services costs over a period of five consecutive years immediately following the most recent medical examination required under paragraph 16(2)(b) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), unless there is evidence that significant costs are likely to be incurred beyond that period, in which case the period is no more than 10 consecutive years; or

-

a demand on health services or social services that would add to existing waiting lists and would increase the rate of mortality and morbidity in Canada as a result of an inability to provide timely services to Canadian citizens or permanent residents.

6.3.1 Excessive demand on Health services

Section R1 defines “health services” as any health services for which the majority of funds are contributed by governments, including the services of family physicians, medical specialists, nurses, chiropractors and physiotherapists, laboratory services and the supply of pharmaceutical or hospital care. The case law has developed separate requirements for excessive demand on health services and excessive demand on social services. Since most health services are publicly funded, without any cost-recovery mechanism, the courts have held that an applicant’s willingness or ability to pay is not a relevant factor. In Deol v. Canada (M.C.I.), 2002 FCA 271, the Federal Court of Appeal said:

“The Minister has no power to admit a person as a permanent resident on the condition that the person either does not make a claim on the health insurance plans in the provinces or promises to reimburse the costs of any services required.”

However, in Companioni v. Canada (M.C.I.), 2009 FC 1315 and later cases, the Federal Court allowed some flexibility in assessing the applicant’s ability to defray the costs of outpatient medication, such as HIV antiretroviral therapy. Therefore, medical officers have to make an individualized assessment of the medical file, the required outpatient medication, the availability of private insurance and the ability to opt out of publicly funded drug plans in the province or territory where the applicant intends to reside.

6.3.2 Excessive demand on Health services

Section R1 defines “social services” as any social services, such as home care, specialized residence and residential services, special education services, social and vocational rehabilitation services, personal support services and the provision of devices related to those services,

- that are intended to assist a person in functioning physically, emotionally, socially, psychologically or vocationally; and

- for which the majority of the funding, including funding that provides direct or indirect financial support to an assisted person, is contributed by governments, either directly or through publicly-funded agencies.

In light of the Supreme Court decision in Hilewitz v. Canada (M.C.I.), De Jong v. Canada (M.C.I.) 2005 SCC 57, and subsequently the Federal Court of Appeal decision in Colaco v. Canada (M.C.I.), 2007 FCA 282, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) officers must consider all evidence presented by an applicant before making a decision of inadmissibility due to excessive demand on social services. The judgments apply to all categories of immigrants.

In Hilewitz and De Jong, the Supreme Court determined that all applicants are entitled to an assessment of the probable demand their disability or impairment might place on social services. The applicant is required to provide the officer with information of sufficient quality and detail to permit an assessment of the probable need for social services. In addition, the applicant may provide evidence of ability and intent to reduce the cost and impact on Canadian social services, and this would have to be considered in making a decision.

6.4 Cost threshold

The cost threshold is determined by multiplying the per capita cost of Canadian health and social services by the number of years used in the medical assessment for the individual applicant. This cost threshold is updated every year.

• For 2021, the cost threshold (under the temporary public policy)$108,990 over 5 years (or $21,798 per year)

• In 2017, the excessive demand cost threshold was $33,275 over 5 years (or $6,655 per year).

• In April of 2018, the Government of Canada made changes to the excessive demand policy and to the cost threshold.

• For 2018, the new cost threshold is $99,060 over 5 years (or $19,812 per year).

How IRCC calculates the cost thresholds, please click here.

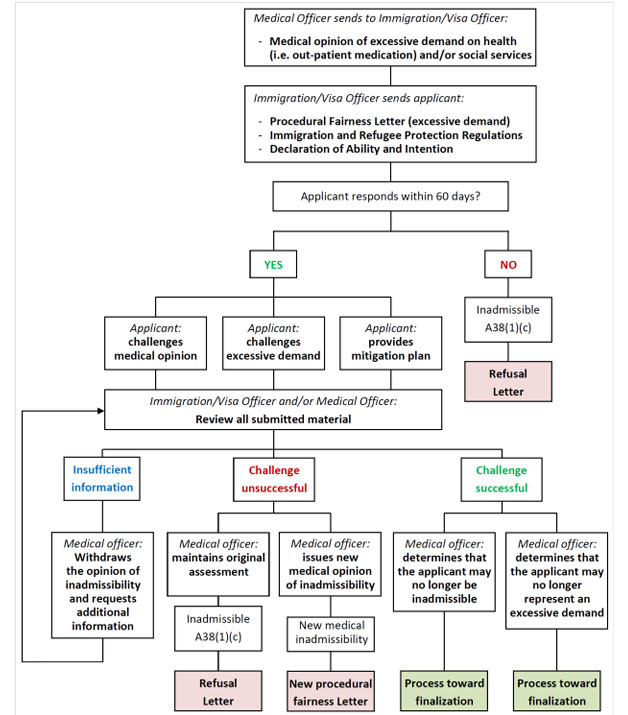

7. Procedural Fairness Protocol

- The medical officer withdraws the opinion of inadmissibility and requests additional information when the applicant’s submissions are insufficient to reach a medical opinion.

- The applicant has provided information that leaves the medical officer in doubt regarding the initial medical assessment; however, the applicant has provided insufficient information to make a final decision. The medical officer should withdraw the current opinion of inadmissibility and request additional information from the applicant in order to reach a new medical assessment.

- The medical officer sends to the immigration or visa officer the medical opinion of excessive demand on health (i.e., outpatient medication) and/or social services.

- The immigration or visa officer sends the applicant

- a procedural fairness letter (excessive demand);

- the IRPR;

- the declaration of ability and intention

The applicant responds within 60 days

- The applicant challenges the medical opinion.

- The applicant challenges the excessive demand.

- The applicant provides a mitigation plan.

- The immigration or visa officer and/or medical officer reviews all submitted material.

- Not successful

- The medical officer maintains original assessment.

- Inadmissible [A38(1)(c)]

- Refusal letter

Or - The medical officer issues new medical opinion of inadmissibility.

- New medical inadmissibility

- New procedural fairness letter

- Successful

- The medical officer determines that the applicant may no longer be inadmissible.

- Process toward finalization

Or - The medical officer determines that the applicant may no longer represent an excessive demand.

- Process toward finalization

- Not successful

The applicant does not respond within 60 days

- Inadmissible [A38(1)(c)]

- Refusal letter

8. Forms, documents and templates

8.1 Immigration Medical Examination

- IMM 5743E – Client Consent and Declaration – To give consent to undergo an immigration medical examination

- IMM 5419E – Medical Report – To medically process immigrant and certain visitor applicants by ports abroad and Canada Immigration Centres

- IMM 5725E – Assessment of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) – Part of the immigration medical examination for some clients

- IMM 5727E – Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) – Part of the immigration medical examination for some clients

- IMM 5728E – Acknowledgement of HIV Post-test Counselling – Mandatory for all clients that test positive for HIV

- IMM 5733E – Instruction for Pregnant Client – X-ray Deferred – Used to defer chest x-rays for pregnant clients

- IMM 5734E – Specialist’s Referral Form – Used to refer client to a specialist

- IMM 5738E – Chart of Early Childhood Development (CECD) – Part of the immigration medical examination for some clients

8.2 Medical surveillance (forms and documents)

8.3 HIV: Automatic partner notifications (documents and template letters)

- Document – Health Follow-Up Handout: HIV Infection (for applicant) – Contact information for HIV specialists in Canada given to clients with HIV

- Document – HIV contact Information in Canada (for sponsor) – Contact information for HIV specialists in Canada given to a sponsor of a client that has HIV

- Document – Automatic Partner Notification Policy (for applicant) – Short summary of the Automatic Partner Notification Policy given to clients

- Sample – Refusal Letter of Sponsorship withdrawal in Family Class

8.4 Medical refusals and procedural fairness (forms, documents and template letters)

8.4.1 Procedural fairness regarding a danger to public health and public safety

Sample – Procedural Fairness Letter (non excessive demand)

8.4.2 Procedural fairness regarding excessive demand on health (i.e., out-patient medication) and/or social services

f you are are concerned with your medicals, or have received a fairness letter, and want to obtain a copy of your medical assessment, or a copy of the medical examination submitted to IRCC, GET GCMS will be happy to procure it for you. Send a message to GET GCMS through our Contact US page to know how to go about obtaining medical documents from IRCC

DISCLAIMER: Our website contains general legal information. The legal information is not advice and should not be treated as such. The legal information on our website is provided without any representations or warranties, express or implied. Further, we do not warrant or represent that the legal information on this website: will be constantly available, or available at all; or is true, accurate, complete, current or non-misleading. No lawyer-client, solicitor-client or attorney-client relationship shall be created through the use of our website.